Aurora Castillo’s story shatters stereotypes about age, heritage, and the role of women in grassroots movements. She began her journey as an activist at age 70, and within a decade, she became one of Los Angeles’ most influential environmental leaders. Her fight wasn’t about abstract climate goals; it was about protecting real neighborhoods, children, and families from toxic threats. This dedication earned her a place in history as the first Latina from Los Angeles to receive the Goldman Environmental Prize. Read more at los-angeles.name.

Biography

Born on January 1, 1914, Aurora Castillo was a fourth-generation Mexican American whose roots were deeply intertwined with the history of Los Angeles. She was the great-great-granddaughter of Augustine Pedro Olvera—one of the city’s original settlers and the namesake of the famous Olvera Street. Castillo built her identity on strong family values, often remarking that family was the center of her universe. Her father, who served as an Army bugler during World War I, was her primary moral compass and an example of lifelong community service.

The Roots of Activism

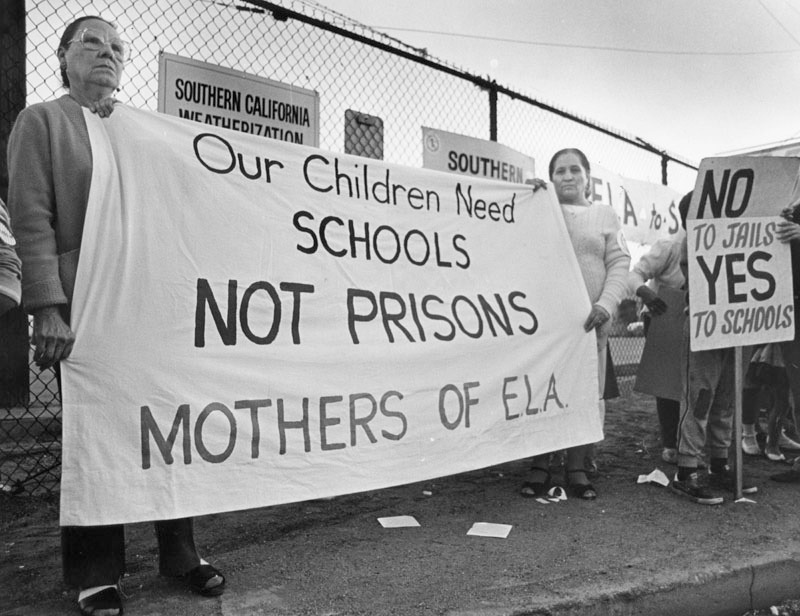

Castillo’s life as a public activist began in 1984 when she was 70 years old. The spark was a proposal to build yet another state prison in Los Angeles—the eighth such facility planned for a predominantly Latino neighborhood. At the request of a local priest, women from the parish joined forces to protest. This alliance gave birth to the Mothers of East Los Angeles, known as MELA. For Castillo and her fellow activists, the core mission was protecting their children and the future of the community. They educated residents on potential risks, organized weekly marches, and built powerful coalitions with other movements, including the Coalition Against the Prison in East Los Angeles.

A defining feature of MELA’s work was the concept of “othermothering.” These women viewed the care of children as a collective responsibility rather than a private family matter. This perspective allowed the community to unite around the shared goal of protecting the health and safety of future generations. For Aurora Castillo, motherhood became a political and environmental category. She saw environmental protection as a natural extension of a mother’s role—caring not just for her own household, but for the entire neighborhood. Under her leadership, MELA focused on East Los Angeles, an area historically burdened by hazardous industrial sites. The group utilized legal challenges, public hearings, and grassroots mobilization to influence city and county decisions. Additionally, she partnered with local educational organizations to promote environmental awareness among youth.

The Fight Against Toxic Threats

By the late 1980s, MELA had evolved into a powerhouse of environmental resistance. In 1984, under Castillo’s guidance, they successfully blocked the construction of a state prison in Boyle Heights, arguing that the facility posed risks to children’s health and local school operations. In 1987, the organization won a high-profile public campaign against the Lancer Incinerator project, which proposed burning municipal waste near residential blocks. Their opposition included testifying at public hearings, circulating petitions, and directly lobbying the California Department of Health Services.

In 1989, MELA teamed up with students from Huntington Park to stop a chemical waste treatment plant. These campaigns became landmarks of successful grassroots activism, proving that local communities could effectively challenge institutional and industrial interests. Over time, the organization expanded its reach, launching water conservation programs, lead poisoning awareness campaigns, and initiatives to help local youth access higher education. These victories are documented by the Goldman Environmental Prize and the California environmental archives, cementing Castillo’s legacy as a pioneer of environmental justice.

International Recognition

In 1995, Aurora Castillo was awarded the Goldman Environmental Prize—the world’s most prestigious honor for grassroots environmentalists. She was the first person from Los Angeles, the first Latina, and the oldest recipient in the prize’s history at that time.

Aurora Castillo passed away from leukemia in 1998. Her legacy continues through the ongoing work of MELA and the broader Los Angeles environmental movement. She proved that activism has no age limit and that protecting the planet begins with caring for people. Her journey from an East LA grandmother to a world-renowned activist remains a symbol of community power, female leadership, and the relentless pursuit of environmental justice.