California is a state synonymous with innovation and a strong commitment to sustainability. The history of hydropower generation plays a critical role in this narrative. Despite its enormous potential for solar and wind power development, California has always had significant hydropower resources. The state’s rivers and waterfalls, for instance, are powerful sources of electricity. You can learn more about this at los-angeles.name.

The Rise of Hydropower

Before the 1900s, hydropower plants supplied about 40% of the electricity in the U.S. By the 1940s, they were generating roughly 75% of all power consumed in the West and Pacific Northwest—accounting for about a third of the nation’s total electricity. These numbers eventually started to decline as other forms of power generation began to expand rapidly.

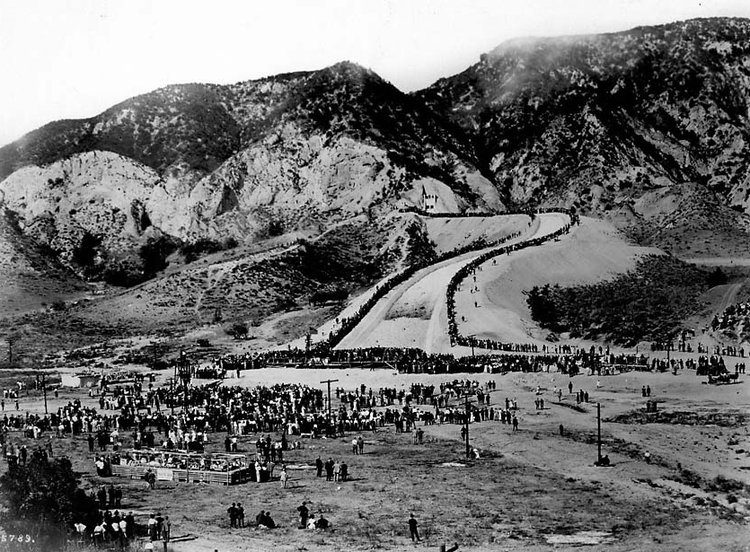

The earliest hydropower plants, built between 1880 and 1895, were direct-current (DC) stations designed to power arc lighting and incandescent lamps. California’s first hydroelectric plant opened in San Bernardino in 1887. The city also saw a 10,000-volt power boost in 1892 thanks to a 42-mile line extension from the plant at San Antonio Creek.

The invention of the electric motor significantly increased the demand for new electrical power, leading to several key developments:

- 1895 to 1915 saw rapid, varied changes in the design and construction styles of hydroelectric plants;

- After World War I, the design of hydropower plants became standardized;

- Most major developments in the 1920s and 1930s were focused on thermal power plants, transmission, and distribution.

Hydropower accounted for 15% of U.S. electricity generation in 1907, rising to about 25% by 1920.

It’s also worth recalling that the Los Angeles Aqueduct was completed in 1913. At the time, it supplied four times the water the city needed, which infamously resulted in the draining of Owens Lake. By paving the way for one of the world’s largest economies, the city’s leadership was forced to confront a harsh reality: fresh water is not an endless resource.

Rapid Growth and Looming Challenges

California achieved statehood in 1850, a process rapidly accelerated by the Gold Rush. Immediately after, the state began constructing vast water control infrastructure, and within a decade, dams and large-scale reclamation districts were established.

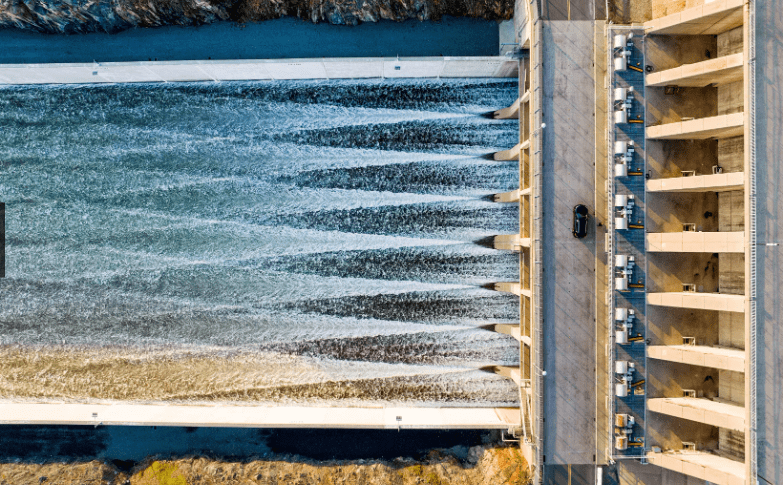

It’s important to note that California operates under two colossal water development systems.

- The State Water Project (SWP), approved by the legislature in 1959. This ambitious project involved building a significant number of dams and aqueducts to pump water from the northern part of the state, which receives more rainfall, to the arid southern regions. Key elements of the SWP include the Shasta Reservoir and the California Aqueduct Canal.

- The Federal Central Valley Project (CVP). This project focuses on irrigating agricultural lands throughout California’s Central Valley. The CVP includes the construction of massive dams, canals, and pumping stations. Key components of the project are the Shasta Reservoir and the Delta-Mendota Canal.

These systems rely on countless reservoirs and dams to store and re-distribute water. Furthermore, the hydropower plants built on these projects generate a significant amount of electricity.

The history of hydropower is detailed in the two-volume set, “The Development of Hydroelectric Power in the United States, 1880-1940”, which was prepared for the Cultural Resource Management Task Force in 1991.

The Renewable Energy Frontier

According to the State Energy Data System, California produces more renewable energy than any other U.S. state except Texas. In 2023, the state demonstrated remarkable success in the renewable energy sector, reaching a milestone where 53% of its electricity generation came from renewable sources.

The severe 2012 drought drastically reduced hydropower production. As a result, the California Energy Commission began tracking drought conditions in 2014. Utilities responded immediately by making market purchases and relying more heavily on other power sources.

At the end of 2016, increased rainfall brought relief from the drought, allowing hydropower plants to return to normal operating conditions.

Hydropower and solar energy have supplied a large portion of the state’s renewable energy. Due to California’s extensive hydrographic network, these sources have traditionally played an essential role in power generation.

In conclusion, California is a U.S. leader in renewable energy development. The state’s achievements in this sector undoubtedly serve as a model for other regions. To continue this trend, California must address several crucial challenges, including grid balancing, adapting to climate change, and meeting the continually rising demand for electricity.