He was one of the 20th century’s most distinguished paleontologists, completely reshaping our understanding of how complex life evolved on Earth. The scientist merged ecology, geology, developmental biology, and genetics to forge a new discipline: paleobiology. This field studies not just individual species, but entire ecosystems of the past. This article covers his main achievements, unique scientific works, groundbreaking theories, fascination with Darwin, and lasting scientific legacy. Find out more at los-angeles.name.

Biography

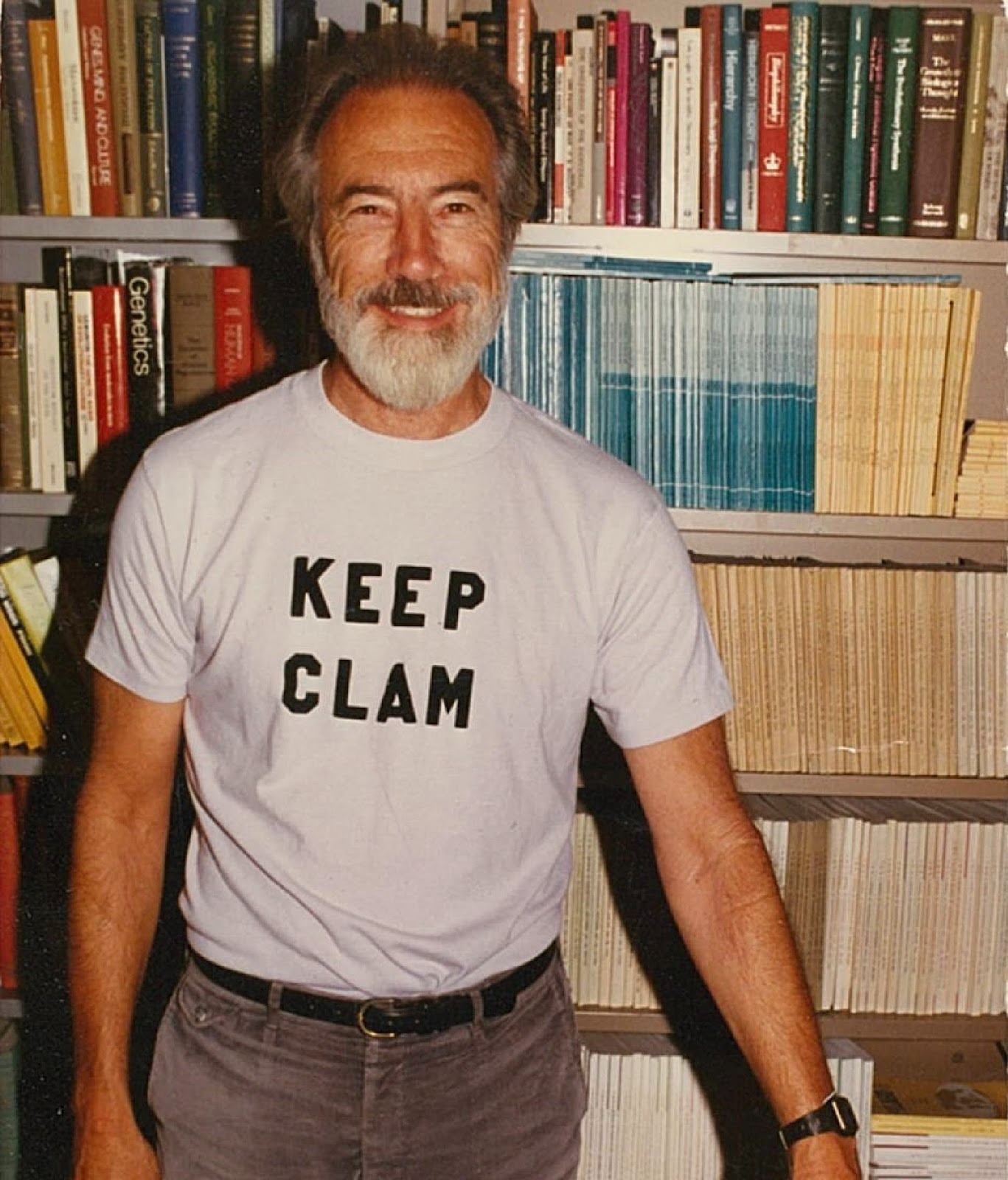

Born in South Los Angeles on November 10, 1926, Valentine grew up in modest circumstances. He was raised by his mother, a music teacher who instilled in him a love for discipline and learning. When World War II broke out, he joined the U.S. Navy and served as a navigator on a landing ship transporting soldiers in the Pacific. After returning in 1945, he used the GI Bill to attend Phillips University in Oklahoma, where he discovered a passion for geology.

He continued his education at UCLA, earning a master’s degree in 1954 and a Ph.D. in paleontology in 1958. While pursuing his studies, he worked for oil companies and researched marine mollusk fossils along the coasts of California and Baja California. Even then, Valentine recognized a crucial fact: evolution could not be understood without considering the ecological context in which organisms lived.

Paleobiology

In the 1960s, Valentine became a key founder of modern paleobiology. He thought like an ecologist, studying how ancient marine communities changed in response to climate, continental drift, and the emergence of new species. Colleagues remember that he saw fossils not just as isolated species, but as members of an ecosystem—some as predators, others as prey. This very approach allowed him to uncover the comprehensive logic behind the development of life on Earth.

One of Valentine’s most daring breakthroughs was connecting plate tectonics to evolution. He was among the first to realize that as continents broke apart, they created new conditions for life: populations became isolated, species evolved independently, and biodiversity was spurred to increase. These ideas were revolutionary for the 1970s, when the theory of plate tectonics itself was only just gaining widespread acceptance. Valentine demonstrated that geological processes shape the planet’s biological history just as profoundly as natural selection does.

Valentine possessed a rare gift for blending intuition with analytical rigor. Colleagues noted he often had a gut feeling for the right answer first and would then find the evidence to back it up—and he was usually correct. His 1973 book, “Evolutionary Paleoecology of the Marine Biosphere,” became a foundational text for modern evolutionary ecology. His students, including Douglas Erwin and David Jablonski, remember that Valentine thought “at the biosphere level.” He didn’t just ask how one species evolved, but how the entire interaction between life and the planet changed over time.

The Cambrian Explosion

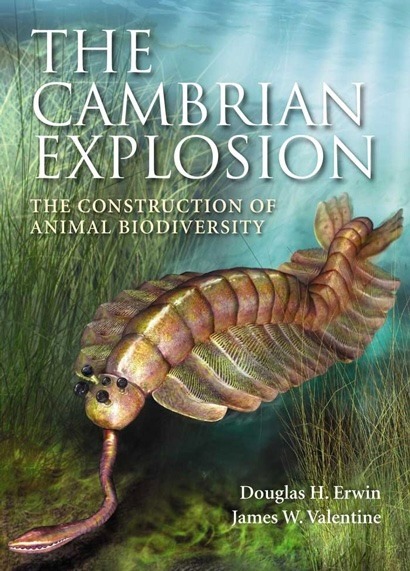

One of Valentine’s central research themes was the mystery of the Cambrian explosion—the sudden burst of species diversity that occurred about 540 million years ago. Collaborating with Douglas Erwin, he investigated how environmental conditions, genetic mechanisms, and cellular development converged to produce complex multicellular life. He demonstrated that this “explosion” was not random but rather the result of a complex interplay between genetic innovation, ecological opportunity, and geological processes. Valentine explored how new developmental genetic toolkits enabled the construction of complex organisms, while environmental changes opened up niches for them to thrive. His 2013 book, “The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity,” was the culmination of decades of research and influenced a new generation of evolutionary biologists.

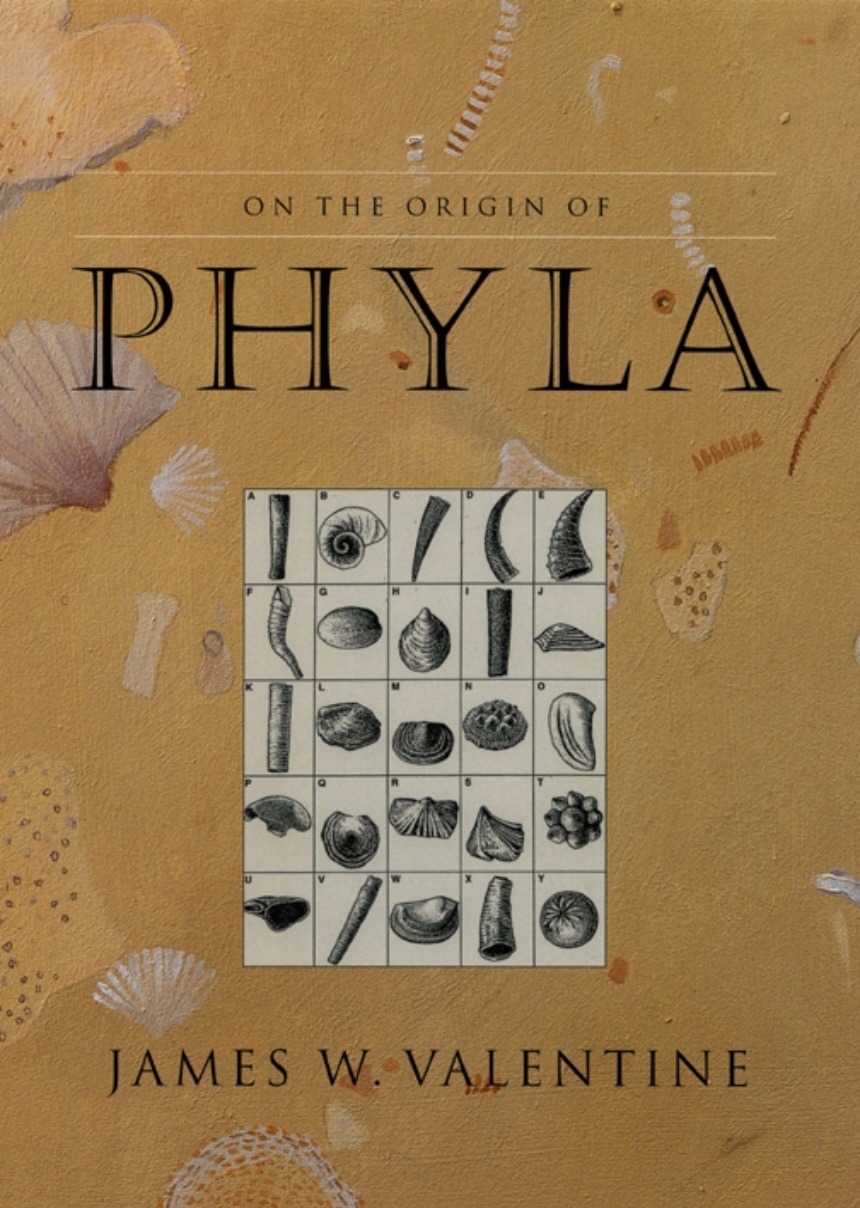

James Valentine always highlighted the scientific heroes who shaped his own views on evolution. He credited George Gaylord Simpson, a preeminent paleontologist whose work on the “modern synthesis” provided a clear framework for understanding life on land. Valentine noted that Simpson’s approach was also invaluable for analyzing Paleozoic marine ecosystems. He had fond memories of his personal interactions with Simpson, recalling that the scientist was always friendly and supportive of young researchers. Valentine was also a passionate admirer of Charles Darwin. He amassed one of the world’s largest collections of On the Origin of Species—over 4,500 volumes, including first editions of 19 of Darwin’s works and 23 translations of his magnum opus. In 2007, he donated this collection to the American Philosophical Society in Philadelphia. He even dedicated his own book, “On the Origin of Phyla” (2004), to Darwin, “as the greatest biologist of all time.”

Despite his worldwide recognition, Valentine remained modest and reserved. He never sought the spotlight, preferring to focus on collaborative research and mentoring young scientists. In his speech accepting the Paleontological Society Medal, he famously thanked his graduate students, calling them his “real teachers.” Valentine was also concerned about trends in science funding. He criticized the tendency to fund massive projects with large teams at the expense of smaller groups or individual researchers. He argued that independent work and quiet observation often spark the unique ideas that drive true creativity. While acknowledging the need for teamwork on big problems, he stressed that preserving “small science” was critical for progress.

Valentine’s key works, which impressed the scientific community and laid the groundwork for a new understanding of evolution, include:

- “Evolutionary Paleoecology of the Marine Biosphere” (1973). This work analyzed changes in marine ecosystems, ecology, and geography, and how they relate to evolutionary processes;

- “On the Origin of Phyla” (2004) — an ambitious attempt to integrate data from paleontology, developmental biology, comparative morphology, and molecular genetics to understand how the major animal body plans appeared;

- “The Cambrian Explosion: The Construction of Animal Biodiversity” (2013) — one of his last major works, synthesizing decades of research and posing critical questions about the origins of complex multicellular life.

Scientific Legacy

Over his lifetime, Valentine wrote or edited six books and published over 200 scientific articles. He was an elected member of the National Academy of Sciences, the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, and the American Philosophical Society. He was also the recipient of prestigious awards, including the Lapworth Medal and the Paleontological Society Medal.

James Valentine passed away on April 7, 2023, in California at the age of 96. His life serves as a powerful example of how one person can fundamentally change our understanding of life’s history. He left behind more than just his research; he left a philosophy of inquiry—the ability to see the connections between the cell’s microworld and global geological processes, between the past and the present, and between science and humanity. His approach bridged geology and biology, showing that Earth’s history and life’s history are one and the same. Valentine believed that understanding this past was the key to predicting the biosphere’s future and preserving its diversity.